As young bachelors in 1840, my great-grandfather’s great uncles, Nineveh and Ephraim Ford, left their native Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina for Missouri, but this would prove to be a temporary stopover as their attention was next drawn to Oregon.

Nineveh’s appetite had been whetted by the scenic descriptions within Lewis and Clark’s account of their great expedition some forty years earlier, and his intention to venture further westward was cemented by information he gleaned from traders and trappers who had been there.

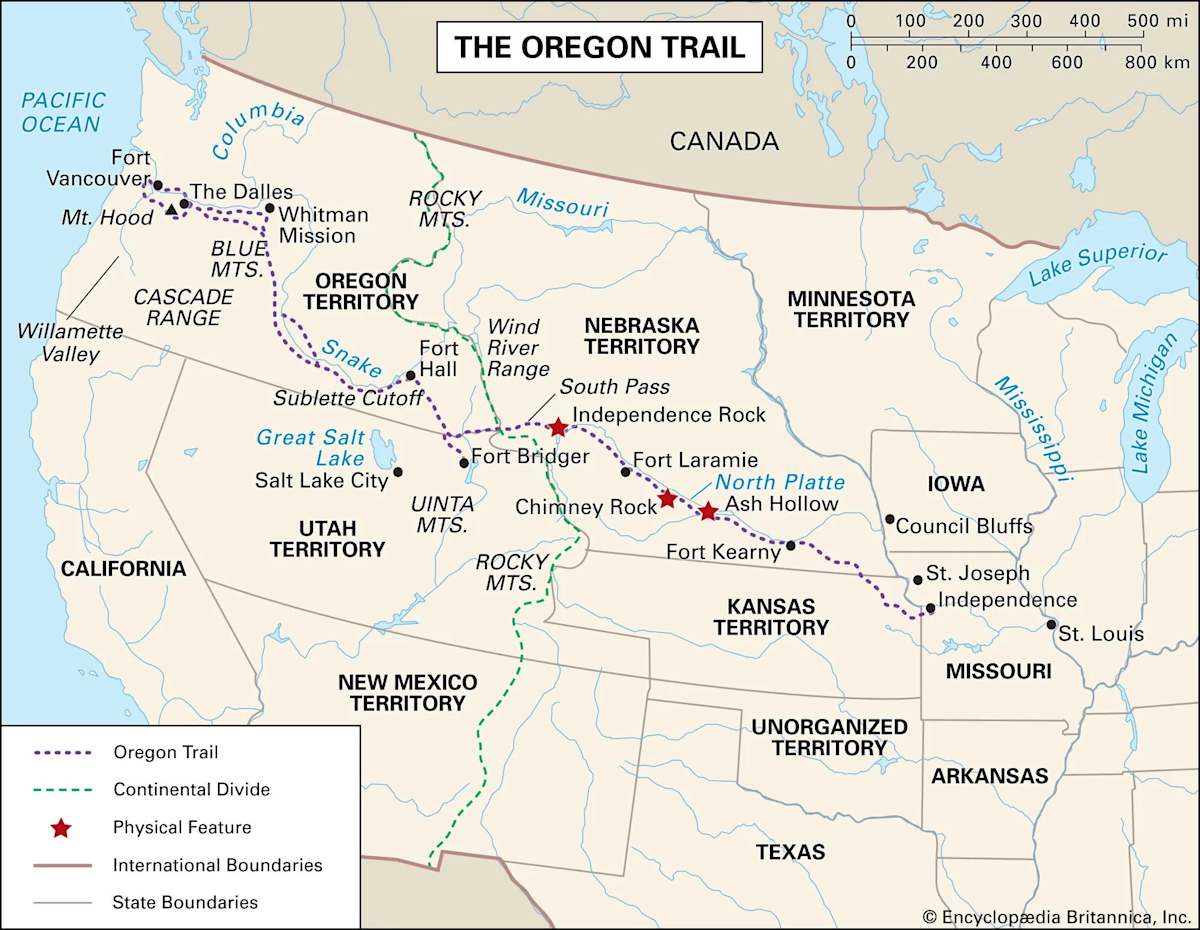

Although it had not yet been fully determined what right the United States had to land west of the Rocky Mountains, a private movement arose in the spring of 1843 among settlers in Platte County, Missouri to colonize Oregon. Fully aware that there was no assurance the federal government would assist or protect them, and that they would be responsible for their own choices and actions, they organized a mission that would become known as “The Great Migration/Wagon Train of 1843.” Between 700 and 1,000 people (including the Ford brothers), with approximately 120 wagons drawn by six-ox teams, and several thousand loose cattle and horses, would be among the first to cross the plains from Missouri.

Before this time, “two or three missionaries had performed the journey on horseback, driving a few cows with them. Three or four wagons drawn by oxen had reached Fort Hall [Idaho]…but it was the honest opinion of most…that no large number of cattle could be subsisted…or wagons taken over a route so rugged and mountainous. The emigrants were also assured that the Sioux would be much opposed to the passage of so large a body through their country and would probably resist it on account of the emigrants destroying and frightening away the buffalo, which were then diminishing in numbers.”

It soon became evident that a group this size could not make satisfactory progress without dividing into two columns – one with cattle and one without – although they continued to travel withing supporting distance of one another. After successfully passing through Indian country with no more trouble than having some animals driven away or stolen, they split into even smaller parties better suited to the narrow mountain paths.

When they came to the Platte River, they made boats from their wagon beds, covering them with cow and buffalo hides, and they swam their animals from bar to bar to gain footing until the crossing was accomplished. After stops at Fort Laramie and Fort Bridger, and after mountainous crossings, including the Black Hills, they reached Fort Hall.

Until this time, they had been led by John Gannt, a former Army officer turned fur trader, who agreed to pilot them there for $1 per person. Afterwards, William Martin succeeded Gannt for a brief time until he parted company at the intersecting California Trail. Although the settlers had been encouraged at Fort Hall to abandon their wagons and use pack animals for the remainder of the journey, Dr. Marcus Whitman, a Christian missionary, who had joined the wagon train at the Platte River, believed they could make whatever road improvements were needed along the way, enabling their wagons to pass through. He volunteered to lead them as far as possible before branching off alone to Walla Walla, Washington, near where he and his wife, Narcissa, had established an outpost that aimed to evangelize the Cayuse Indians.

Near American Falls, at the first crossing of the Snake River, Whitman advised the expedition to fasten their teams together, and everyone except Nineveh Ford followed his instruction. Thinking he had a strong carriage that could hold its own, he fell in behind the other wagons and teams, which, as they entered the river, caused the water level to heighten. Soon, the current pressed so hard against Nineveh’s team that it almost drove them over the shoal where several persons and animals had been known to drown. Sensing the danger, he leapt from his carriage, pressed himself against his team, and held his lead ox in place until the other wagons had completely crossed over and the water lowered.

Riding back, Whitman threw Nineveh a rope and told him to place it around the lead ox’s horns. With the other end of the rope tied around his saddle, Whitman towed the team across the water while Nineveh steered his carriage. (Nineveh felt Whitman had saved his life, and he particularly contemplated this four years later when Whitman, his wife, and eleven others were massacred by the Cayuse at their Walla Walla mission.)

Although Whitman had to leave the wagon train en route, he did not abandon them but instructed them how to proceed from place to place until they reached the Grande Ronde Valley, at which point he sent an Indian to guide them onwards to Walla Walla.

The settlers encountered no serious trouble from Fort Hall to the Grande Ronde, and although they sometimes had to climb mountains, battle sagebrush and sandy ground (which tended to bog down the wagons and tire the teams), or choose which divide would take them in the right direction, it was mostly open country.

The settlers had timed their expedition so that they left Missouri in the spring, traveled throughout the summer, and reached the Grande Ronde in September before encountering snow. Crossing the Grande Ronde and the Blue Mountains meant nearing the end of their journey. By the time they crossed the Grande Ronde River, they were met with an early snowfall, but the two inches quickly melted. The country was so beautiful that, if they had had the necessary provisions, they might have elected to colonize there.

Upon encountering the Blue Mountains, they had to chop their way through thick timber. It was a laborious task. Their axes had become dull as they had no access to a grinding stone since they departed Missouri, and their hands were blistering and tender. Though getting late in the season, the lazier men dropped back, claiming the need to rest their cattle, while the bulk of the work fell upon the shoulders of forty men, who persevered in driving the wagons and cutting out a road. The timber became lighter and more scattered near the top of the mountains, and the descent down the other side was comparatively easier.

From there, they proceeded to Umatilla and then to Whitman’s Station near Walla Walla. All the while, they had followed the guidance of the Indian that Whitman had sent to them. Ironically, as Nineveh would recall, this was the very Indian who later killed Whitman.

After a few days at Whitman’s, they continued down the Columbia River. Some of the party attempted to make the journey in canoes constructed of unmanageable cottonwood, and, traveling to The Dalles, most were capsized, some being thrown onto the rocks, while others were sent down the rapids, resulting in a loss of both lives and possessions.

Meanwhile, Nineveh had remained with the wagons, leading the caravan with his own wagon, which was the first to reach The Dalles. This was as far as they could go by wagon, because the Cascade Mountains separated them from the Willamette Valley, and there was no road around Mt. Hood. Several of the men went into the pine forest, obtained trees, used their oxen to haul them to the river, and constructed rafts. They then took their wagons apart and placed them, alongside their possessions, on the rafts to continue their journey until their landing at the Cascades, where they spent two weeks making a wagon road around the mountains.

Nineveh subsequently brought the first wagons down the river below the Cascades, and he did so by lashing together four canoes to make a raft, using five wagon beds to make a platform on top of the canoes, and placing the wagons’ disassembled running gears and baggage on top of the platform. In the center, he hoisted a mast with a wagon sheet for a sail.

The odd craft drew a great deal of attention and comical remarks; some observers doubted it could withstand the trip. But Nineveh was confident in it and his ability to manage it, and with the assistance of two Native American men and two white men, they successfully sailed to Vancouver, Washington. The first man to meet Nineveh once he stepped ashore was Dr. John McLoughlin (later known as “The Father of Oregon”), who complimented him for his perseverance – for traveling as far as possible by land and then inventing a way of traveling further by water.

After gathering supplies, the five men continued down the Columbia River to the mouth of the Willamette River, where they encountered a strong gale of wind that generated six-foot high waves, slushing over their raft, cargo, and heads. As Nineveh steered the raft and attempted to keep it in the smoother, middle portion of the river, his four comrades went to bail water out of the canoes. They traveled very quickly upstream until they reached the rapids below Oregon City, where the winds subsided and they docked for the night.

The following morning, November 10, 1843, they towed the raft over the rapids with ropes and reached Oregon City, bringing the first cargo of wagons that ever reached that location by land or by sea.

Uncle Nineveh Ford (whose picture as an older man accompanies this post) subsequently married and had a large family, helped establish the first Baptist congregation in the Northwest, fought in wars against the Cayuse and Nez Perce Indians, settled and farmed in the Walla Walla Valley, and served three terms as a state senator and twice as a county commissioner. He died in 1897.

As for Uncle Ephraim Ford, he was a very pious man, who settled in Yamhill County, Oregon, married there, and raised a family. In 1857, he suffered what seems to have been a sort of mental breakdown and was on the verge of being placed in a California asylum for the insane; thankfully, the episode lasted only two months. Seven years later, in 1863, after losing control of the horses pulling his carriage, he jumped to avoid crashing and broke his leg. Sadly, gangrene set in, and the limb was amputated, but he died following the surgery.

What remarkable things these pioneering brothers must have seen and experienced during their transcontinental journey from North Carolina to Oregon!