More than a decade before the War Between the States, a smaller scale war was waged between brothers Jesse and James Ward that would stretch on for more than five years and would eventually be ruled upon by the North Carolina Supreme Court.

The brothers were sons of Benjamin Ward, a Virginia native and Revolutionary War veteran, who had made his home in western North Carolina by 1777. Benjamin was among the first settlers on lower Watauga River in Ashe (present-day Watauga) County. He died in 1820, and by the time of the two brothers’ conflict, six of Benjamin’s ten children were also deceased, the four survivors being Daniel (who had moved to Virginia), Kelly (who had long since relocated to Middle Tennessee), and Jesse and James, who remained in Watauga County.

Because Watauga County had been newly created in 1849 and perhaps did not have a fully operational court system for a period of time, Jesse submitted a bill of complaint in the spring of 1850 to the Ashe County Court of Equity against his brother James. That fall, James was summoned to the courthouse in Jefferson to respond. Over the course of the next year, Jesse’s complaint progressed into a lawsuit against James, and in the fall of 1851, the case was transferred to the Watauga County Superior Court of Equity.

The brothers’ trouble arose over a 50-acre tract of land on Cove Creek, which Jesse said he had inherited from their father’s estate. Jesse proclaimed himself to be “a man of weak judgment and understanding, [who] could be easily persuaded” and stated that, around 1827, he actually had been persuaded by James (who employed “many artful devices and false representations”) and others recruited by James to convey the land to James. Jesse said James agreed to pay him $300 for the land over a three-year period, and if James failed to pay the full amount within that timeframe, possession of the land was to revert to Jesse.

According to Jesse, despite his repeated requests for James to either pay him the agreed upon $300 or return the land to him, James refused, continuing to claim it as his own and alleging that Jesse “was not capable of attending to his own business.” Feeling cheated and defrauded, Jesse sought relief from the court. Due to his low net worth and his inability to pay the security required for the prosecution of the case, the court granted Jesse pauper status and assigned him legal counsel, and Jesse’s father-in-law, William Shupe, assisted with the case as Jesse’s agent.

In response to his brother’s complaint, James Ward appears to have initially stated, “I had no notion of buying the land, but Jesse Ward took a liking to a fine stable horse of mine and said he believed he would give [me] his land for the horse. I do not recollect anything about Jesse Ward or myself going to Bedent Baird’s to get him to write a deed, for I had no idea of making a contract with him for the land.” At some other point in time, however, James stated that the conveyance of the 50 acres transpired in August 1829, that Jesse had been planning to sell the land to Joseph Shull (James’s brother-in-law) for $300, but Jesse decided he would be willing to sell it to James instead. James agreed to pay the $300 on “long credit” over a five-year period. According to James, Jesse accepted these terms, and Bedent Baird, a mutual friend, drafted the deed at the home of James’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Mary Shull, and in the presence of Mary’s children, Joseph and Elizabeth Shull (future wife of Noah Mast). James further stated that the deed was unconditional and made without qualifications, and there was no such agreement between him and Jesse that, if James failed to pay the $300, the land would return to Jesse. James did not believe he had the power to persuade Jesse to deed the land. He said he used no artful devices, false representations, or manipulation to induce his brother, and Jesse entered the agreement deliberately and of his own free will.

At the time the deed was written, both Jesse and James were in their late twenties/early thirties. A bachelor, Jesse had lived with James and his wife and children for about a decade (since circa 1820 when their father died) and continued to do so for more than a decade afterward (until circa 1841), at which time Jesse married and started his own family. James brought up the fact that, when Jesse married, he continued making his home on James’s land and was a trespasser, repossessing a portion of the disputed land.

In order to demonstrate that he had paid Jesse, at least in part, for the land by means other than directly giving him cash, James stated that, a short time before the 1829 land deed, Jesse had purchased two horses from him for $100, and James had afterwards let Jesse have two other horses (also valued at $100), four milk cows (valued at $40), and a rifle (valued at $12). James further stated he had paid more than $100 to cover Jesse’s debts to Boone, North Carolina merchant Jordan Councill [Jr.], both before and after the land deed. In James’s mind, this meant he had extended Jesse more than $252 toward the $300 he owed Jesse for the land.

In terms of any balance he owed Jesse, James said Jesse had been further indebted to him for travel expenses, lawyers’ fees, etc. that James had incurred and services he had performed in an 1839 attempt to recover a portion of an estate that the brothers believed were due them. In fact, Jesse, in a written document, had appointed James as his “true and lawful attorney” to represent his interests in the matter. In 1833, their father’s younger brother, Dr. William Ward, a wealthy physician and landowner, who resided in Rutherford County, Tennessee near Nashville, died. Having no children and no surviving siblings, the court determined Dr. Ward’s estate should be distributed among his widow and any surviving blood nieces and nephews (which included Jesse and James, although at the time of Dr. Ward’s death, the identities of Benjamin Ward’s children were unknown to the court). [In anticipation of the brothers’ embarking upon their claim on their uncle’s estate, Joseph Mast gave sworn testimony in 1839 before Bedent Baird and Reuben Mast, justices of the peace, regarding his 40+ decades of acquaintance with the brothers and their being sons and heirs of Benjamin Ward and nephews of William Ward. That same day, Baird also swore to the same before Reuben Mast.] According to James, he and Jesse jointly employed Bedent Baird to accompany James to Tennessee to investigate the brothers’ heirship, and James paid Baird $75, half of which Jesse was to reimburse James but was unable to. Jesse was also to have paid James $100 for his own trouble and expenses.

Finally, James said that, for a period of months in early 1840, he furnished Jesse’s board and clothing, half of which Jesse had agreed to reimburse but never did. James estimated that his loss of time and expenses involved in providing Jesse with these services was worth at least $75. James stated that, in consideration of their relationship as brothers, he did not demand full satisfaction from Jesse for his indebtedness, and that the two of them reached a settlement in which Jesse’s debts would be applied to what James owed him for the land. James said they further agreed Jesse would be discharged from future indebtedness to James in return for Jesse relinquishing the land to James without requiring James to pay for it. According to James, Jesse surrendered the bond (which outlined the terms of what James owed for the land) to him, and it was cancelled by virtue of James tearing up the bond in Jesse’s presence.

By the commencement of this lawsuit, almost a quarter of a century had passed since Jesse deeded the land to James, and almost a decade had transpired since the 1840 debt settlement that James said he and Jesse had reached. In light of this passage of time, James believed the court should take into consideration the statute of limitations for bringing such actions.

In the spring of 1852, court clerk James W. Councill began issuing subpoenas to summon witnesses, and these were executed by the county sheriff – initially by Sheriff John “Jack” Horton and later by succeeding Sheriff D. C. McCanles. This process continued periodically for more than three years and through the summer of 1855, with some witnesses being recalled more than once. The witnesses were ordered to appear at the home of Benjamin Councill, and they were to provide depositions in the varying presences of Reuben Mast, Thomas Hodges, Lorenzo Dow Whittington, and Benjamin Councill, justices of the peace. [Although Watauga County’s first courthouse had been built in 1850, the Councill residence – the county’s first brick house, which stood approximately upon the present-day site of Brown’s Used Cars along Highway 421 in Vilas – may have been chosen because it was in closer proximity to the western Watauga dwellings of the majority of witnesses and would reduce travel time and perhaps ensure their attendance.]

The witness list was ultimately comprised of thirty-four individuals, many of whom were among Watauga County’s earliest residents and interrelated by blood and/or marriage: Bedent Baird and his sons Euclid, Alexander, Franklin, Palmer, and Rittenhouse Baird; Joseph Shull, his sister, Elizabeth Shull Mast, and her husband Noah Mast (brother of justice of the peace Reuben Mast); brothers Samuel and William Hix and their nephews David and Adam Hix; Jordan Councill [Jr.] and his brother and sister-in-law, Benjamin and Temperance Shull Councill (a sister to Joseph Shull and Elizabeth Shull Mast); Gilbert Hodges (father of justice of the peace Thomas Hodges) and his son Robert Hodges; John Teaster and his brother Ransom Teaster; Malden C. Harmon, his mother, Rhoda Harmon, his father-in-law, John J. Whittington (father of justice of the peace Lorenzo Dow Whittington), John Whittington’s uncle by marriage, Moses Hately, and Moses’ sons-in-law, Frederick “Fred” Danner and Nathan Kernels; Jehiel Smith; Samuel Swift; Henry Taylor; Jack Horton; Jacob Guerly; Simon Ward (James Ward’s son); John and Rebecca Ward Walker (James Ward’s son-in-law and daughter); and Amos Ward (Jesse and James Ward’s nephew). [The nearly 150 pages of documents associated with this case do not include testimonies from Malden C. and Rhoda Harmon, Jehiel Smith, Samuel Swift, Henry Taylor, Jacob Guerly, or Benjamin and Temperance Shull Councill. Perhaps their depositions were lost, or perhaps they were not ultimately called upon.]

The witnesses, many of whom lived within a mile or two of the Ward brothers and were well acquainted with them, swore upon “the Holy Evangelist of God Almighty” and commenced answering questions. Because Bedent Baird was so interwoven within the claims of the brothers, he was naturally an important witness and the first to be called. Baird testified that he was present at the execution of the will of Benjamin Ward (Jesse’s and James’s father), and at that time, land deeds of sale were made to his children. According to Baird, “The old man Benjamin Ward said at the time that he did not wish those lands to be sold out of the family.” Baird said he wrote the deeds, including the one to Jesse, and that that deed included the land that Jesse later sold to James. Baird testified that these were deeds of conveyance for the full value of the land, and part of the purchase money was paid at the time of their issue with the balance to be made payable to Benjamin Ward.

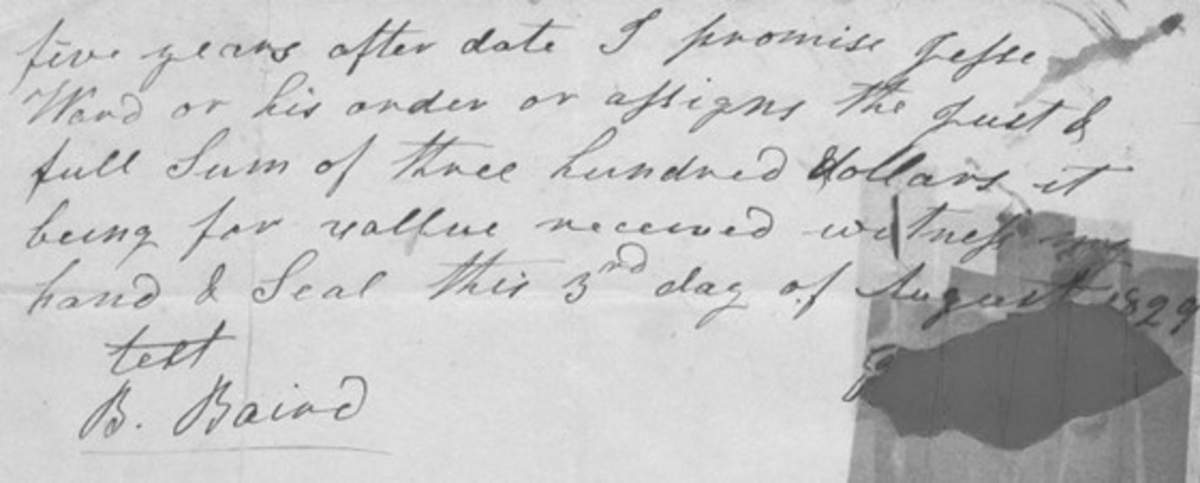

Baird also testified that he was present at the execution of a deed of conveyance from Jesse Ward to James Ward in 1829, and that James gave Jesse a note in consideration of the purchase money, which was $300. [Later, as a recalled witness, Baird further stated that James had actually been in possession of the land before the contract was made between him and Jesse, but he did not know for how long. Baird also testified that, at the request of the parties, he had written the deed of conveyance between Jesse and James as well as the note or bond. In fact, the actual note was produced and is the image accompanying this story.] Baird did not recollect any conversation between him and the Ward brothers at the time of the deed’s execution concerning the contract being conditional or the land being reconveyed to Jesse if James failed to pay for it within a certain timeframe. Baird stated that he had known Jesse Ward since Jesse was a child and had known him to be of sound mind and discretion and considered him to be a man competent to dispose of his property, make contracts, and transact the common business of life.

James Ward’s son, John, testified that he heard Jesse say James purchased this land from him, and that James gave Jesse a note for $300. Elizabeth Shull Mast testified likewise, adding that she had witnessed the bond by which James was to pay Jesse $300 for the land within a three-year period, and if the money was not paid, the land was to be Jesse’s again. She stated that nothing was said about how the money was to be paid, but it was regarded as a cash transaction. She said she had frequently heard James say Jesse was not capable of managing his own matters, and James had asked her to persuade Jesse to let him have the land.

Regarding the Ward brothers’ pursuit of their share of their late uncle’s estate, which occurred ten years after the land transaction, Bedent Baird testified that he heard Jesse tell James that, if James would take Baird with him to Tennessee and endeavor to recover their joint interest in the estate, he would pay James $100. Baird agreed to go and stated he and James were gone for about a month. When Baird was recalled as a witness several months later, he stated that his recollection of his trip to Tennessee with James was not very good, but he again remembered a contract being made in which Jesse was to pay James $100 if James could employ him [Baird] to make the trip with James. Baird did not recall Jesse and James ever speaking of this $100 as a payment for Jesse’s land, or if the contract was conditional, or whether James was to be paid out of any funds he was to receive from the Tennessee estate, which Baird stated was a failure. Baird said he later sued James for $30-40 to recover his own services in the matter.

James Ward’s children, Simon Ward, John Ward, and Rebecca Ward Walker, corroborated Baird’s testimony, stating they had been present when the discussion occurred concerning the estate in Tennessee and that their uncle Jesse was to give their father $100 for making the trip, taking Bedent Baird with him, and paying expenses. John Ward added that the $100 was to be credited on the note his father had given Jesse for the land if his father did not get paid for his trouble and expenses. He stated that his father did go to Tennessee, but he did not know if he ever got anything for his trouble.

Just as Bedent Baird and Elizabeth Shull Mast had been asked about Jesse Ward’s mental capacity, many of the subsequent witnesses were similarly questioned. Among those (in addition to Bedent Baird) who, based on their own personal interactions with Jesse, said they believed him to be a competent man of ordinary sense and judgment, who was capable of trading, making contracts, and transacting his own business were his son Simon, his son-in-law John Walker, David Hix, Adam Hix, Jack Horton, and Alexander, Palmer, and Rittenhouse Baird. Palmer Baird stated that, although he had “never had more but a half a dollar’s dealing with him,” he believed Jesse was capable of managing his own affairs with common prudence. Other of these witnesses added that Jesse was very circumspect in his dealings, always endeavoring to make the best of a bargain and to the best advantage.

Others, however, said the converse was true. According to the cumulative testimonies of Noah Mast, Jordan Councill [Jr.], Moses Hatley, Samuel Hix, Amos Ward, Euclid Baird, Gilbert Hodges, and John J. Whittington – most of whom had known Jesse for decades – Jesse was a weak-minded man, who was never able to handle his own business and who could easily be imposed upon by others, including those he placed confidence in. Some of these witnesses, as well as Robert Hodges and Fred Danner, understood that Jesse was not able to manage the disputed land, and that James Ward desired to take possession of it for safekeeping and to prevent Jesse “from fooling it away.” Noah Mast stated that he knew Jesse to frequently offer exorbitant prices for articles, the value of which was generally known. Samuel Hix added that he had never known Jesse to do any trading while he was living with James unless James consented to it. Moses Hatley testified that he heard James say he had been appointed Jesse’s guardian.

Jordan Councill [Jr.] testified that he had known Jesse Ward for forty years and that Jesse’s account with him had been running for more than fifteen of those years. Councill said Jesse owed him upwards of $150, primarily for clothing (jeans cloth, domestics’ hats, shoes, and so forth), and that, contrary to what James Ward had said, James never paid him any money or property on Jesse’s behalf. John J. Whittington, who had also known Jesse for four decades, testified that he knew Councill’s character to be good for veracity and truth and would be compelled to believe anything Councill stated upon oath.

But Simon Ward contradicted Jordan Councill’s testimony, saying he heard Councill state on at least two occasions that James had paid him $85-100 toward what Jesse owed Councill. John Walker testified likewise, saying that Councill, at James’s house and in the presence of James’s family and Alexander Baird, said that James had paid him a large sum of money on Jesse’s behalf. This was corroborated by Alexander Baird, who said he heard Councill state that James had paid him $75-80, maybe even $100, for Jesse’s debts.

In regard to whether James Ward ever paid Jesse for the land, Moses Hatley stated he never heard anything about it, but David Hix said he had diverse conversations with Jesse about selling his land to James, and that Jesse told him James had pretty well paid him for it. Euclid Baird testified that James said he had paid Jesse for the land by boarding him ever since their father died.

As to the Ward brothers’ living and farming together, Noah Mast testified that Jesse labored on James’s farm like a regular hand. Samuel Hix said he knew nothing of Jesse ever being paid wages, but according to the Wards’ nephew, Amos Ward (who lived with them at the time the land deed was made), a portion of their corn crop was allotted to Jesse annually. On one occasion, when Hix had gotten two bushels of corn from Jesse, James collected the pay for it. According to Hix, James once said, “If Jesse was let alone, he would give away everything on the plantation.”

In terms of the land in question, some witness testimony seemed to indicate that, although Jesse had sold the land to James, Jesse, by virtue of his residing on James’s farm, continued to benefit from it and had, within the last dozen years, perhaps even repossessed it or a portion of it. According to Ransom Teaster, when Jesse began cultivating the land, he was living on another piece of James’s land, higher up on the river. [This was probably following Jesse’s marriage, at which point James had stated Jesse continued living on his land, but as a trespasser.] As long as Teaster could remember, James had owned the land, and Teaster did not know how Jesse had regained possession of it. Of the disputed land, Teaster stated Jesse had, for ten years, cleared about six acres of bottom land and three acres of meadow. He said an additional 1.5 acres had been cleared, but he did not know who cleared it.

Bedent and Rittenhouse Baird also testified they were familiar with the land in controversy, and that Jesse had been in possession of it for the past ten to twelve years, although prior to that time, Jesse and James were living on the land together and “cropping it.” Bedent did not, however, believe this was the full 50-acre tract, and Rittenhouse believed Jesse had cultivated six or seven acres of bottom land and three to four acres of additional land, including an acre or two of meadow land, while James was in possession of about three acres of tillable land. Rittenhouse was not aware of any rental contract between the Ward brothers, and Bedent did not know if Jesse was in the habit of paying James one-third of all that he made upon this land. According to Rittenhouse, Jesse had “made tolerable fair crops of corn and oats,” but neither he nor Bedent could state what the value of one-third of those crops would be. Both Bedent and Rittenhouse estimated the full disputed tract to have an annual worth of $40-50, and Bedent stated that, in terms of improvements upon the land, about 1.5 acres were cleared, a log house was moved from James’s land and put up there, and one other small house was erected, along with a little fencing.

Contrary to the Bairds’ estimated valuation, Noah Mast thought the disputed land’s yearly value to be no more than $20. According to Mast, in some years Jesse utilized the land to yield 150-200 bushels of corn, a good crop of oats, and sometimes wheat and rye, but the year prior to Mast’s testimony, he believed Jesse had not brought in more than 75 bushels of corn. According to witness Nathan Kernels, the land was part good and part sorry, and according to how lands were renting in the county, he thought its full value would be $15-20.

James’s son, John Ward, stated he had worked on the land in question, and that Jesse disposed of his share of their crop for his own use and did not let his father have any of it. Of the disputed fifty acres, John said his father was currently in possession of about three acres of it. He did know if this included any woodland but had seen his father cutting wood and timber on the land. He said his father hired Jesse to cut rails for him, and Jesse cut them off of that land. John also stated that, while Jesse was cultivating the land, he did not know if his father claimed it and had ever since heard it called “disputed land” that Jesse claimed as his own. He did not think Jesse had ever paid his father any rent for the land, nor was rent demanded. He also did not believe it to be understood that rent for this land was to be regarded as a payment of the original $300 purchase price. When asked if he would be willing to give $50 cash for the rent of this land, John stated he thought he would. He further stated that he could not say what Jesse’s average crop was upon the land.

Although Amos Ward had no knowledge of Jesse receiving two horses and four cows from James, Simon Ward and his sister, Rebecca Ward Walker, stated this was true and occurred after the land deed. Simon said the two bay mares were worth $65 each and the four cattle were worth $10 per head, but he did not know if Jesse paid anything for them. Simon added that Jesse was living with James at the time and used the horses on James’s farm. He said they were in Jesse’s possession for several years before they died.

Taking these many depositions into consideration, the state Supreme Court, ruled on the case from Morganton, North Carolina in the fall of 1855. Although James had asked the court to consider the statute of limitations as it regarded the timing of Jesse’s lawsuit against him, the court determined it to be ten years, and because James stated he and Jesse had previously reached a settlement in April 1840, and Jesse filed his original complaint in March 1850, it was within the ten-year limit.

Although Jesse had claimed that, if James did not pay him for the land, the land was to be reconveyed to Jesse, the only witnesses who supported this claim in their testimony were Joseph Shull and his sister, Elizabeth Shull Mast. The court, however, placed no confidence in Elizabeth’s testimony. Although she stated she was present when the contract was made, that she was a subscribing witness to the bond, and that the bond was to be paid in within three years, when the actual bond was produced, it was proven that she was not a witness to it and that it was payable in five years rather than three. The court wrote, “We can put no reliance on the recollections of a witness whose memory is so treacherous.”

The court’s opinion supported James’s allegation that the sale of the land was absolute and without any conditions, and the court further stated that, based on witness testimony, the sale price of the land was fair and there was no proof that Jesse’s mind was so weak that he was exposed to imposition or importunity by those in whom he had confidence. But the court also found that James did owe some money to Jesse for the land in the amount of $201.60. Of that, $160 was principal (the original $300 minus $140 for the two horses and four cattle James had given Jesse), and $41.60 was interest accrued over an 8.5-year time period between August 1834 and January 1843. Despite this award, Jesse filed exceptions to the ruling. One exception was that the value of the two horses had been allowed as payment on the note. Another exception was that the court clerk had allowed James rent for the land for the last twelve years from 1843 to 1855 as a payment of interest upon the note. The court overruled Jesse’s exceptions, and the long-drawn-out case finally reached its end.

These two Ward siblings continued to live in close proximity to one another in Watauga County until their deaths – Jesse's sometime after 1870 and James's in 1878, but there seems to be no further record of the condition of their relationship or whether these brothers at odds were ever reconciled.

[Author’s Note: Almost all those involved in this case are my kin. Jesse and James Ward are my uncles. So are Dr. William Ward, Joseph Shull, Noah and Reuben Mast, Samuel and William Hix, and Jordan Councill [Jr.]. Bedent Baird, Euclid Baird, and Rittenhouse Baird are my uncles by marriage as well as my cousins. Elizabeth Shull Mast is my aunt. Rhoda Harmon is my aunt by marriage. Benjamin Ward, Joseph Mast, Mary Mast, Jack Horton, and Benjamin and Temperance Shull Councill are my direct grandparents. James W. Councill, Alexander Baird, Palmer Baird, Franklin Baird, David Hix, Adam Hix, John Teaster, Ransom Teaster, Malden C. Harmon, Gilbert Hodges, Thomas Hodges, Robert Hodges, Simon Ward, Rebecca Ward Walker, and Amos Ward are my cousins. Lorenzo Dow Whittington, John Walker, Henry Taylor, and D. C. McCanles married my cousins. Many of these individuals were also closely connected to my ancestor Cutliff Harman. The wives of Bedent Baird and of Duke and Benjamin Ward, Jr. (Jesse and James Ward’s brothers) were Cutliff’s daughters. Rhoda Harmon was Cutliff’s daughter-in-law. Samuel and William Hix’s sister was another of Cutliff’s daughters-in-law. The wives of Joseph Shull, Henry Taylor, Reuben Mast, and Lorenzo Dow Whittington were Cutliff’s granddaughters. Euclid, Rittenhouse, Alexander, Palmer, and Franklin Baird, as well as Malden C. Harmon and Amos Ward were Cutliff’s grandsons.]